Unicode UTF-16 is the “native” Unicode encoding used in Windows. In particular, the UTF-16LE (Little-Endian) format is used (which specifies the byte order, i.e. the bytes within a two-byte code unit are stored in the little-endian format, with the least significant byte stored at lower memory address).

Often the need arises to convert between UTF-16 and UTF-8 in Windows C++ code. For example, you may invoke a Windows API that returns a string in UTF-16 format, like FormatMessageW to get a descriptive error message from a system error code, and then you want to convert that string to UTF-8 to return it via a std::exception::what overriding, or write the text in UTF-8 encoding in a log file.

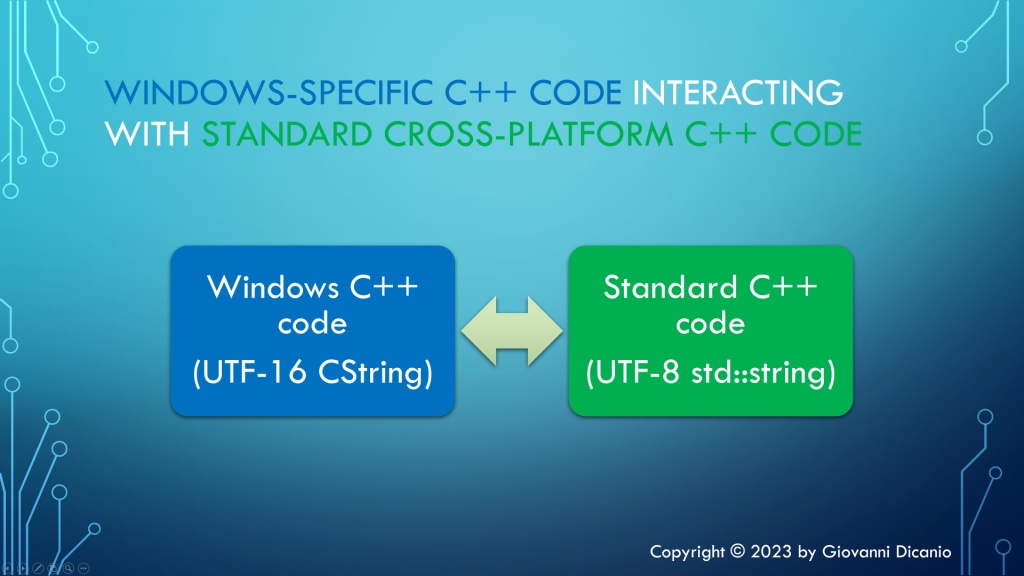

I usually like working with “native” UTF-16-encoded strings in Windows C++ code, and then convert to UTF-8 for external storage or transmission outside of application boundaries, or for cross-platform C++ code.

So, how can you convert some text from UTF-16 to UTF-8? The Windows API makes it available a C-interface function named WideCharToMultiByte. Note that there is also the symmetric MultiByteToWideChar that can be used for the opposite conversion from UTF-8 to UTF-16.

Let’s focus our attention on the aforementioned WideCharToMultiByte. You pass to it a UTF-16-encoded string, and on success this API will return the corresponding UTF-8-encoded string.

As you can see from Microsoft official documentation, this API takes several parameters:

int WideCharToMultiByte(

[in] UINT CodePage,

[in] DWORD dwFlags,

[in] LPCWCH lpWideCharStr,

[in] int cchWideChar,

[out, optional] LPSTR lpMultiByteStr,

[in] int cbMultiByte,

[in, optional] LPCCH lpDefaultChar,

[out, optional] LPBOOL lpUsedDefaultChar

);

So, instead of explicitly invoking it every time you need in your code, it’s much better to wrap it in a convenient higher-level C++ function.

Choosing a Name for the Conversion Function

How can we name that function? One option could be ConvertUtf16ToUtf8, or maybe just Utf16ToUtf8. In this way, the flow or direction of the conversion seems pretty clear from the function’s name.

However, let’s see some potential C++ code that invokes this helper function:

std::string utf8 = Utf16ToUtf8(utf16);

The kind of ugly thing here is that we see the utf8 result on the same side of the Utf16 part of the function name; and the Utf8 part of the function name is near the utf16 input argument:

std::string utf8 = Utf16ToUtf8(utf16);

// ^^^^ =====

//

// The utf8 return value is near the Utf16 part of the function name,

// and the Utf8 part of the function name is near the utf16 argument.

This may look somewhat intricate. Would it be nicer to have the UTF-8 return and UTF-16 argument parts on the same side, putting the return on the left and the argument on the right? Something like that:

std::string utf8 = Utf8FromUtf16(utf16);

// ^^^^^^^^^^^ ===========

// The UTF-8 and UTF-16 parts are on the same side

//

// result = [Result]From[Argument](argument);

//

Anyway, pick the coding style that you prefer.

Let’s assume Utf8FromUtf16 from now on.

Defining the Public Interface of the Conversion Function

We can store the UTF-8 result string using std::string as the return type. For the UTF-16 input argument, we could use a std::wstring, passing it to the function as a const reference (const &), since this is an input read-only parameter, and we want to avoid potentially expensive deep copies:

std::string Utf8FromUtf16(const std::wstring& utf16);

If you are using at least C++17, another option to pass the input UTF-16 string is using a string view, in particular std::wstring_view:

std::string Utf8FromUtf16(std::wstring_view utf16);

Note that string views are cheap to copy, so they can be simply passed by value.

Note that when you invoke the WideCharToMultiByte API you have two options for passing the input string. In both cases you pass a pointer to the input UTF-16 string in the lpWideCharStr parameter. Then in the cchWideChar parameter you can either specify the count of wchar_ts in the input string, or pass -1 if the string is null-terminated and you want to process the whole string (letting the API figure out the length).

Note that passing the explicit wchar_t count allows you to process only a sub-string of a given string, which works nicely with the std::wstring_view C++ class.

In addition, you can mark this helper C++ function with [[nodiscard]], as discarding the return value would likely be a programming error, so it’s better to at least have the C++ compiler emit a warning about that:

[[nodiscard]] std::string Utf8FromUtf16(std::wstring_view utf16);

Now that we have defined the public interface of our helper conversion function, let’s focus on the implementation code.

Implementing the Conversion Code

The first thing we can do is to check the special case of an empty input string, and, in such case, just return an empty string back to the caller:

// Special case of empty input string

if (utf16.empty())

{

// Empty input --> return empty output string

return std::string{};

}

Now that we got this special case out of our way, let’s focus on the general case of non-empty UTF-16 input strings. We can proceed in three logical steps, as follows:

- Invoke the WideCharToMultiByte API a first time, to get the size of the result UTF-8 string.

- Create a std::string object with large enough internal array, that can store a UTF-8 string of that size.

- Invoke the WideCharToMultiByte API a second time, to do the actual conversion from UTF-16 to UTF-8, passing the address of the internal buffer of the UTF-8 string created in the previous step.

Let’s write some C++ code to put these steps into action.

First, the WideCharToMultiByte API can take several flags. In our case, we’ll use the WC_ERR_INVALID_CHARS flag, which tells the API to fail if an invalid input character is encountered. Since we’ll invoke the API a couple times, it makes sense to store this flag in a constant, and reuse it in both API calls:

// Safely fail if an invalid UTF-16 character sequence is encountered

constexpr DWORD kFlags = WC_ERR_INVALID_CHARS;

We also need the length of the input string, in wchar_t count. We can invoke the length (or size) method of std::wstring_view for that. However, note that wstring_view::length returns a value of type equivalent to size_t, while the WideCharToMultiByte API’s cchWideChar parameter is of type int. So we have a type mismatch here. We could simply use a static_cast<int> here, but that would be more like putting a “patch” on the issue. A better approach is to first check that the input string length can be safely stored inside an int, which is always the case for strings of reasonable lengths, but not for gigantic strings, like for strings of length greater than 2^31-1, that is more than two billion wchar_ts in size! In such cases, the conversion from an unsigned integer (size_t) to a signed integer (int) can generate a negative number, and negative lengths don’t make sense.

For a safe conversion, we could write this C++ code:

if (utf16.length() > static_cast<size_t>((std::numeric_limits<int>::max)()))

{

throw std::overflow_error(

"Input string is too long; size_t-length doesn't fit into an int."

);

}

// Safely cast from size_t to int

const int utf16Length = static_cast<int>(utf16.length());

Now we can invoke the WideCharToMultiByte API to get the length of the result UTF-8 string, as described in the first step above:

// Get the length, in chars, of the resulting UTF-8 string

const int utf8Length = ::WideCharToMultiByte(

CP_UTF8, // convert to UTF-8

kFlags, // conversion flags

utf16.data(), // source UTF-16 string

utf16Length, // length of source UTF-16 string, in wchar_ts

nullptr, // unused - no conversion required in this step

0, // request size of destination buffer, in chars

nullptr, nullptr // unused

);

if (utf8Length == 0)

{

// Conversion error: capture error code and throw

const DWORD errorCode = ::GetLastError();

// You can throw an exception here...

}

Now we can create a std::string object of the desired length, to store the result UTF-8 string (this is the second step):

// Make room in the destination string for the converted bits

std::string utf8(utf8Length, '\0');

char* utf8Buffer = utf8.data();

Now that we have a string object with proper size, we can invoke the WideCharToMultiByte API a second time, to do the actual conversion (this is the third step):

// Do the actual conversion from UTF-16 to UTF-8

int result = ::WideCharToMultiByte(

CP_UTF8, // convert to UTF-8

kFlags, // conversion flags

utf16.data(), // source UTF-16 string

utf16Length, // length of source UTF-16 string, in wchar_ts

utf8Buffer, // pointer to destination buffer

utf8Length, // size of destination buffer, in chars

nullptr, nullptr // unused

);

if (result == 0)

{

// Conversion error: capture error code and throw

const DWORD errorCode = ::GetLastError();

// Throw some exception here...

}

And now we can finally return the result UTF-8 string back to the caller!

You can find reusable C++ code that follows these steps in this GitHub repo of mine. This repo contains code for converting in both directions: from UTF-16 to UTF-8 (as described here), and vice versa. The opposite conversion (from UTF-8 to UTF-16) is done invoking the MultiByteToWideChar API; the logical steps are the same.

P.S. You can also find an article of mine about this topic in an old issue of MSDN Magazine (September 2016): Unicode Encoding Conversions with STL Strings and Win32 APIs. This article contains a nice introduction to the Unicode UTF-16 and UTF-8 encodings. But please keep in mind that this article predates C++17, so there was no discussion of using string views for the input string parameters. Moreover, the (non const) pointer to the string’s internal array was retrieved with the &s[0] syntax, instead of invoking the convenient non-const [w]string::data overload introduced in C++17.