I have been using Visual Studio for C++ development since it was still called Visual C++ (and was a 100% C++-focused IDE), starting from version 4 (maybe 4.2) on Windows 95. I loved VC++ 6. Even today, Microsoft Visual Studio is still my first choice for C++ development on Windows.

In addition to that, I wanted to use VS Code for C++ development for some course work. Why choosing VS Code? Well, in addition to being free to use (as is the Visual Studio Community Edition), another important point of VS Code in that teaching context is its cross-platform feature: in fact, it’s available not only for Windows, but also for Linux and Mac, and students using those platforms could easily follow along.

I had VS Code and the MS C/C++ extension already installed on one of my PCs. I wrote some C++ demo code that used some C++20 features. I tried to build that code, and I got some error messages, telling me that I was using features that required at least C++20. Fine, I thought: Maybe the default C++ standard is set to something pre-C++20 (for example, VS 2019 defaults to C++14).

So, I pressed Ctrl+Shift+P, selected C/C++ Edit Configurations (UI), and in the C/C++ Configurations page, selected c++20 for the C++ standard.

Then I pressed F5 to start a debugging session, preceded by a build process, and saw that the build process failed.

I took a look at the error message in the terminal window, and to my surprise the error messages were telling me that some libraries (like <span>) were available only with C++20 or later. But I had just selected the C++20 standard a few minutes ago!

So, I double-checked, pressing Ctrl+Shift+P and selecting C/C++ Edit Configurations (UI), and in the C/C++ Configurations, the selected C++ standard was c++20, as expected.

I also took a look at the c_cpp_properties.json, and found that the “cppStandard” property was properly set to “c++20”, as well.

Despite these confirmations in the UI, I noted that in the terminal window, on the command line used to build the C++ source code, the option to set the C++20 compilation mode was not passed to the C++ compiler!

So, basically, the UI was telling me that the C++20 mode was enabled. But the C++ compiler was invoked in a way that did not reflect that, as the flag enabling C++20 was not specified on the command line!

I also tried to close and reopen VS Code, double-checked things one more time, but the results were always the same: C++20 was set in the C/C++ Configurations UI and in the c_cpp_properties.json file, but compilation failed due to the C++20 option not specified on the command line when invoking the C++ compiler.

I thought that this was a bug, and opened an issue on the MS C/C++ Extension GitHub page.

After some time, to my surprise, I noted that the issue was closed as “by design”! Seriously? I mean, what kind of good reasonable intuitive design is the one in which the UI tells you that you have selected a given C++ language standard, but the command line doesn’t compile your code according to that??

This is the comment associated to the closing of the issue:

This is “by design”. The settings in c_cpp_properties.json do not affect the build. You need to set the flags in your tasks.json or other source of build info (CMakeLists.txt etc.).

So, am I supposed to manually set the C++20 flag in the tasks.json, despite having already set it in the C/C++ Configurations UI? Well, I do think that is either a bug, or a bad and confusing design choice. If I set the C++20 option in the UI, that should be automatically reflected on the command line, as well. If a modification is required to tasks.json to enable C++20, that should have been the job of the UI, in which I had already selected the C++20 standard!

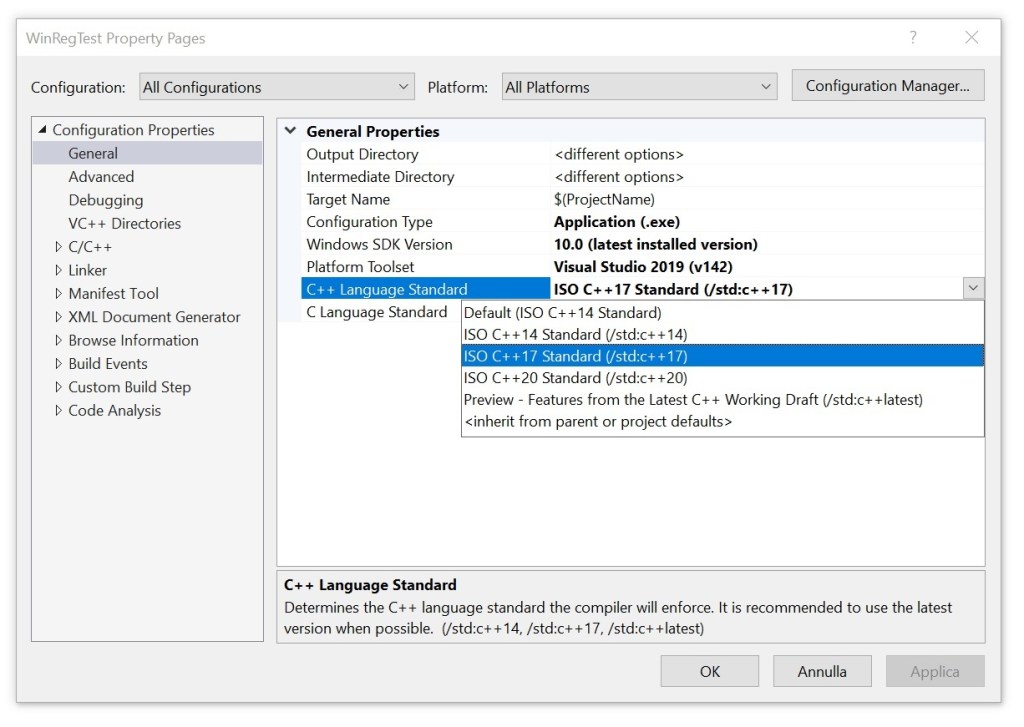

Compare that to the sane intuitive behavior of Visual Studio, in which you can simply set the C++ standard option in the UI, and the IDE will invoke the C++ compiler with the proper flags, reflecting that.