My previous enumeration of the various string options available in C++ was by no means meant to be fully exhaustive. For example: Another interesting option available for programmers using C++17 and successive versions of the standard is std::string_view, with all its variations along the lines of what I described in the previous post (e.g. std::wstring_view, std::u8string_view, std::u16string_view, etc.).

I wanted to dedicate a different blog post to string_view’s, as they are kind of different from “ordinary” strings like std::string instances.

You can think of a string_view as a string observer. The string_view instance does not own the string (unlike say std::string): It just observes a sequence of contiguous characters.

Another important difference between std::string objects and std::string_view instances is that, while std::strings are guaranteed to be NUL-terminated, string_views are not!

This is very important, for example, when you pass a string_view invoking its data() method to a function that takes a C-style raw string pointer (const char *), that assumes that the sequence of characters pointed to is NUL-terminated. That’s not guaranteed for string views, and that can be the source of subtle bugs!

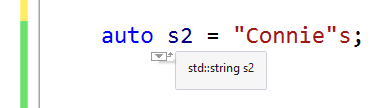

Another important feature of string views is that you can create string_view instances using the sv suffix, for example:

auto s = "Connie"sv;

The above code creates a string view of a raw character array literal.

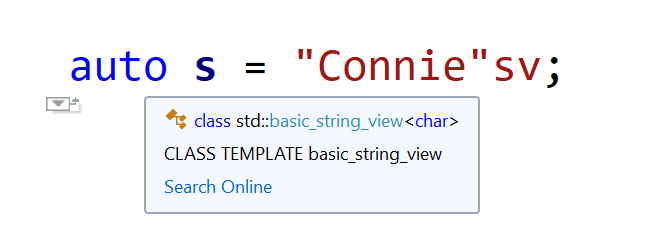

And what about:

auto s2 = L"Connie"sv;

This time s2 is deduced to be of type std::wstring_view (which is a shortcut for std::basic_string_view<wchar_t>), thanks to the L prefix!

And don’t even think you are done! In fact, you can combine that with the other options listed in the previous blog post, for example: u8“Connie”sv, LR”(C:\Path\To\Connie)”sv, and so on.