The previous article on enumerating modules loaded into a process using Win32 API functions and C++ invites/inspires some reflections and pieces of advice on using modern C++ at the Win32 API boundaries.

#1: Raw C Handles Should Be Wrapped in Safe C++ Classes (a.k.a. Raw C Handles Are Radioactive)

Many Win32 API C-interface functions use raw C handles (e.g. represented by the HANDLE type). For example, we saw in the previous article that the CreateToolhelp32Snapshot function returns a HANDLE that we used with other related API functions to enumerate the loaded modules.

When the handle is not needed anymore, for example after the enumeration process is completed (or even if it’s interrupted by an error), the raw handle must be freed calling the CloseHandle Win32 API function. This is a common pattern for lots of Win32 API functions:

HANDLE hSomething = CreateSomething( /* ...various parameters... */ );

// Check that the handle is valid

// (a typical error value is INVALID_HANDLE_VALUE)

// Do some processing with the above handle

DoSomething(hSomething, /* ...various parameters ... */);

// Close the handle at the end of the elaboration

CloseHandle(hSomething);

// Avoid dangling references to handles already closed

hSomething = INVALID_HANDLE_VALUE;

Well, in modern C++ the idea is to wrap this raw C HANDLE in a safe C++ class, such that, when instances of this class go out of scope, the handle will be automatically closed.

That is made possible by the fact that the C++ class destructor will be automatically called when instances of the class go out of scope, so a proper call to CloseHandle can be made by the destructor itself (or by some cleanup helper method invoked by the destructor).

To be safe, the cleanup code should also take into account the case in which the wrapped handle is invalid (case represented by the INVALID_HANDLE_VALUE for the CreateToolhelp32Snapshot API function discussed above).

So, the initial skeleton code for such a wrapper C++ class could look like this:

//----------------------------------------------------

// C++ class that safely wraps a raw C-style HANDLE,

// and releases it when instances of the class

// go out of scope.

//----------------------------------------------------

class ScopedHandle

{

public:

// Gain ownership of the input raw handle

explicit ScopedHandle(HANDLE h) noexcept

: m_handle{h}

{}

// Get access to the wrapped raw handle,

// for example to pass it as an argument

// to other Win32 API functions

HANDLE GetHandle() const noexcept

{

return m_handle;

}

// Safely releases the wrapped handle

// (if the handle is valid)

~ScopedHandle() noexcept

{

if (m_handle != INVALID_HANDLE_VALUE)

{

::CloseHandle(m_handle);

}

}

private:

// Wrapped raw handle

HANDLE m_handle;

};

As I discussed in more details in my course on Practical C++ 14 and C++17 Features (that can be still applied to newer versions of the C++ standard, as well), you can think of the raw handle as something “radioactive”, that should be safely wrapped in RAII boundaries, provided by a C++ class that behaves as a resource manager, like the one shown above.

Moreover, to avoid subtle bugs, it’s important to prevent copies for a class like the one described above:

class ScopedHandle

{

//

// Disable Copy

//

private:

ScopedHandle(ScopedHandle const&) = delete;

ScopedHandle& operator=(ScopedHandle const&) = delete;

...

(If you do want to make the class copyable, it’s important that copy operations are well defined and implemented; for example, you could use some form of reference count applied to the wrapped handle.)

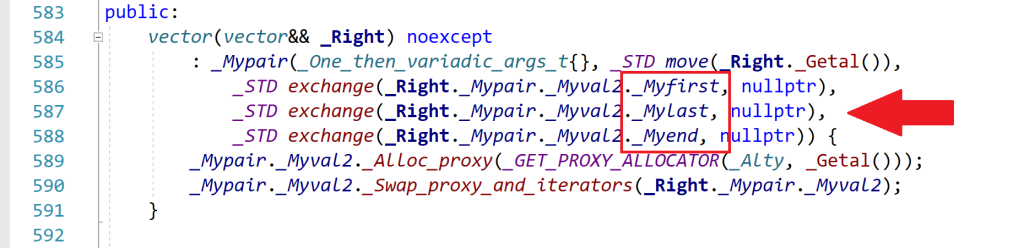

It’s also possible to improve this kind of resource manager class, for example adding move semantics. That would make it possible, for example, to return a wrapped handle by some factory function, or store it in containers like std::vector. In such case the class name should be changed to reflect its improved nature (ScopedHandle wouldn’t work anymore); for example, we could name it SafeHandle, or UniqueHandle (if it’s movable but not copyable), or whatever you like best.

If you want to see some C++ compilable code for a resource manager class like that, you can take a look at the winreg::RegKey class of my WinReg C++ library (you can find the code in the header-only WinReg.hpp file). Note that, in this case, the wrapped raw handle is of type HKEY (i.e. a handle to a registry key).

The code can be generalized, as well. For example, you could write a generic SafeHandle<T> template. This could be the topic of some future articles.

Moreover, if you want to reuse something already available, the Microsoft WIL open-source library provides a wil::unique_handle template for that purpose.

Whatever class or template you choose to use or write, the bottom line is: Do not use raw handles in modern C++ code; wrap them in safe “RAII” boundaries provided by C++ resource manager classes.

#2: Use C++ String Classes Instead of Raw C-style Null-terminated Character Arrays

Win32 API functions usually work with C structures that represent strings using either raw C-style null-terminated character pointers, or null-terminated character arrays.

In modern C++, you can do better than that! In fact, you can use safe and convenient C++ string classes instead of working with those more basic raw C-style constructs.

For example, the MODULEENTRY32 structure used in the previous article on module enumeration, has two fields that are WCHAR C-style raw null-terminated character arrays: szModule and szExePath.

// Structure definition from MSDN:

// https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/win32/api/tlhelp32/ns-tlhelp32-moduleentry32w

typedef struct tagMODULEENTRY32W {

DWORD dwSize;

...

// Null-terminated WCHAR arrays representing Unicode UTF-16

// strings in C:

WCHAR szModule[MAX_MODULE_NAME32 + 1];

WCHAR szExePath[MAX_PATH];

} MODULEENTRY32W;

Instead of working with those, you can create instances of C++ string classes, like CString or std::wstring, and operate on those much safer and higher level constructs made available by the C++ language and libraries:

MODULEENTRY32 moduleEntry;

...

// Create a string object storing the module name

std::wstring moduleName(moduleEntry.szModule);

// Can use ATL/MFC CString as well:

CString moduleName(moduleEntry.szModule);

Once you have created string objects from those C raw character arrays, forget about the original C character arrays, and use only the C++ string objects in the rest of your modern C++ code.

C++ string classes have many advantages over pure raw C-style arrays of characters, like being easily and safely copyable. They can also be concatenated with a very simple and highly readable syntax, like using the operator+ overload (as in: s1 + s2). And they are properly freed when they go out of scope, as well.

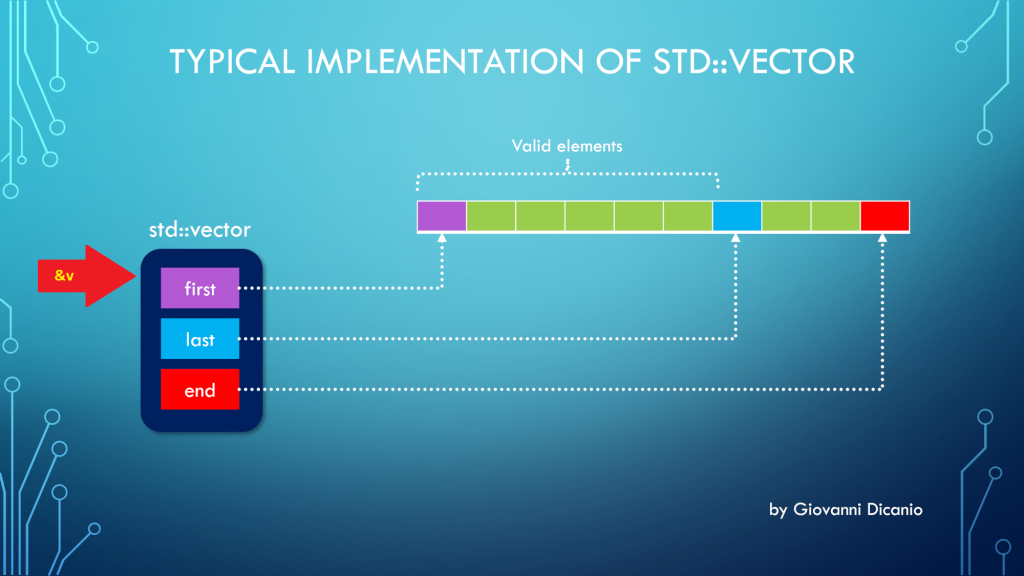

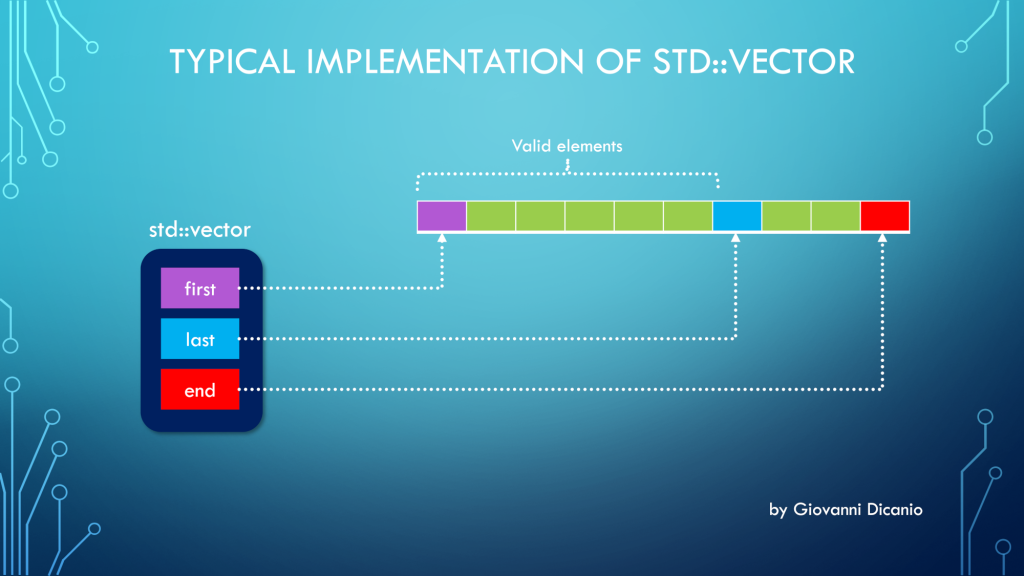

#3: Use C++ Containers Like std::vector Instead of Raw C Arrays

If you take a look at MSDN examples, that are typically written in C, you’ll see lots of uses of raw C arrays to store a set of elements. Typically the code follows this pattern:

SOME_STRUCTURE elements[MAX_COUNT];

// May have another variable representing

// the actual number of elements stored in the array.

// This is increased when a new element is added.

int elementCount = 0;

In modern C++, you can do better than that: In fact, you can create a std::vector containing instances of the structures, and you can dynamically grow the vector, for example adding new elements to it invoking its push_back method:

// Start creating an empty vector

std::vector<ModuleInfo> loadedModules;

// When a new module is found during the enumeration,

// add it to the vector container

loadedModules.push_back( ModuleInfo{ /* ... */ } );

Hope you find these suggestions of some interest!

C is a great language for the “boundaries”. But you can happily switch gears to modern C++ on your own side of the boundary.