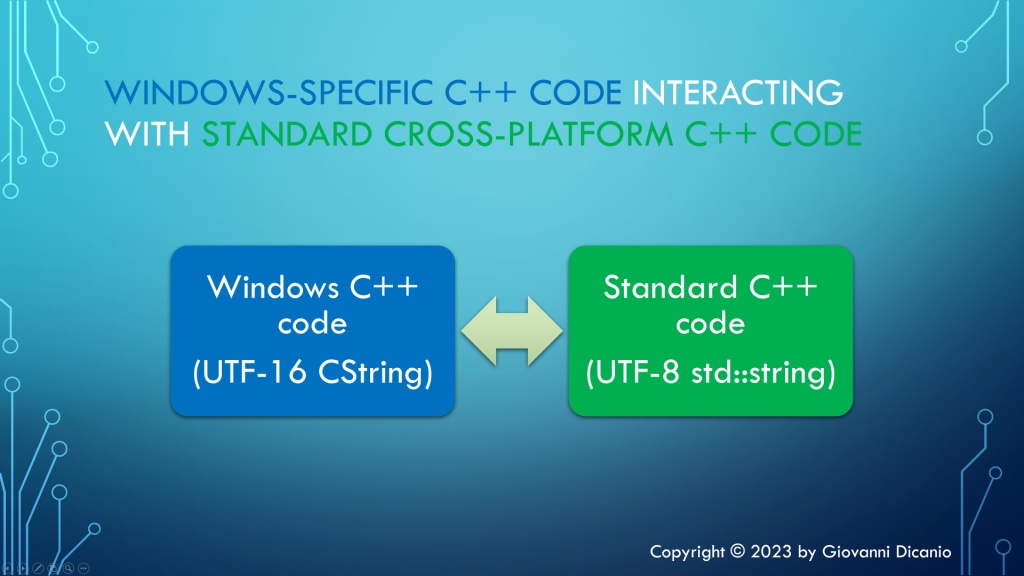

In previous articles we saw some options for using STL strings and ATL/MFC CString at the Windows API boundaries. Let’s do a quick refresher and comparison between these two “worlds”.

For the sake of simplicity, let’s assume Unicode builds (which have been the default since VS 2005) and consider std::wstring for the STL side of the comparison.

The Input String Case

When passing strings as input parameters to Windows API C-interface functions, you can invoke the c_str method for STL std::wstring instances; on the other side, you can just pass CString instances, as CString implements an implicit C-style string pointer conversion operator, that will be automatically invoked by the compiler. At first sight, it seems that the CString approach is simpler (i.e. just pass the CString object), although in modern C++ there is a propensity to avoid implicit conversions, so the explicit call to c_str required by STL strings sounds safer. (Anyway, if you prefer explicit method invocations, CString offers a GetString method, as well.)

The Output String Case

Using an External Temporary Buffer – Both STL strings and ATL/MFC CString have constructor overloads that take an input pointer to a raw character buffer that is assumed to be null-terminated, and can build string objects from the content of that raw C-style null-terminated character buffer. This means that you can create an external temporary character buffer, pass a pointer to it as output string parameter to the C-interface Windows API you want to invoke, and then build the result string object (both STL wstring and ATL/MFC CString) using a pointer to that external intermediate buffer. In addition, an explicit buffer length can be passed together with the pointer to the beginning of the buffer, in case you want or need to explicitly pass the string length, and not relying on the null terminator.

Working In-Place – For both STL strings and ATL/MFC CString it’s possible to work with an internal buffer. This can be allocated using the resize method for STL strings, and then can be accessed via the non-const pointer returned by the data method invoked for the same string. If the returned string is shorter than the allocated buffer length, you have to find the position of the null-terminator scribbled in by the invoked Windows API, and call the STL string’s resize method once again to set the proper size (“length”) of the result string object.

On the other hand, with CString you can use the GetBuffer/ReleaseBuffer method pair: You can allocate the internal CString buffer specifying a proper (minimum) size invoking GetBuffer, then pass the pointer it returns on success to Windows C-interface APIs, and finally invoke CString::ReleaseBuffer to let the CString object update its internal state to properly store the null-terminated string written by the called function into the provided buffer.

Summary Table of the Various Cases

The following table summarizes the various cases discussed so far in a compact form:

I think that for the “working in-place” output sub-case, CString is more convenient than STL strings, as:

- You don’t have to specify any initial value for filling the buffer allocated with GetBuffer; on the other hand, with STL strings you must specify some initial value to fill the string buffer when you invoke the string’s resize method (or equivalently the string constructor that takes a count of characters to repeat). So the CString::GetBuffer method is also likely more efficient, as it doesn’t need to fill the allocated buffer (at least in release builds).

- It’s possible to allocate a larger-than-needed buffer with GetBuffer (all in all you pass the safe minimum required buffer length to this method), then have the Windows API function write a shorter null-terminated string in that buffer. The ReleaseBuffer method will automatically scan the buffer content for the string’s null-terminator, and will properly update the CString object internal state (e.g. the string length) in accordance to that. This nice feature (scan until the null-terminator and properly set the string size) is not available with STL strings, as there is no such thing as a resize_until_null method.

A Small Suggestion for Improving STL Strings Interoperability with C-Interface Functions (Including Windows APIs)

So, here’s as a small suggestion for improving the C++ standard library strings: It would be nice to have something like get_buffer and release_buffer methods available for STL strings, following the same semantics of CString’s GetBuffer and ReleaseBuffer methods, with:

1. No need to specify an initial character to fill the STL string object when the internal buffer is allocated.

2. Automatically set the size of the final string object based on the null-terminator written into the internal buffer.