Some reflections on the use (or abuse?) of the [[nodiscard]] attribute introduced in C++17.

An interesting addition made in C++17 has been the [[nodiscard]] attribute. The basic idea is to apply it such that the C++ compiler will emit a warning when the return values of functions or methods are discarded.

Someone said that, even in previous versions of the C++ standard, if your C++ compiler didn’t emit a warning when you discard the return value of functions or methods, you should discard that C++ compiler.

Really?

Well, consider this simple piece of C++ code:

int GetSomething()

{

return 10;

}

int main()

{

GetSomething();

}

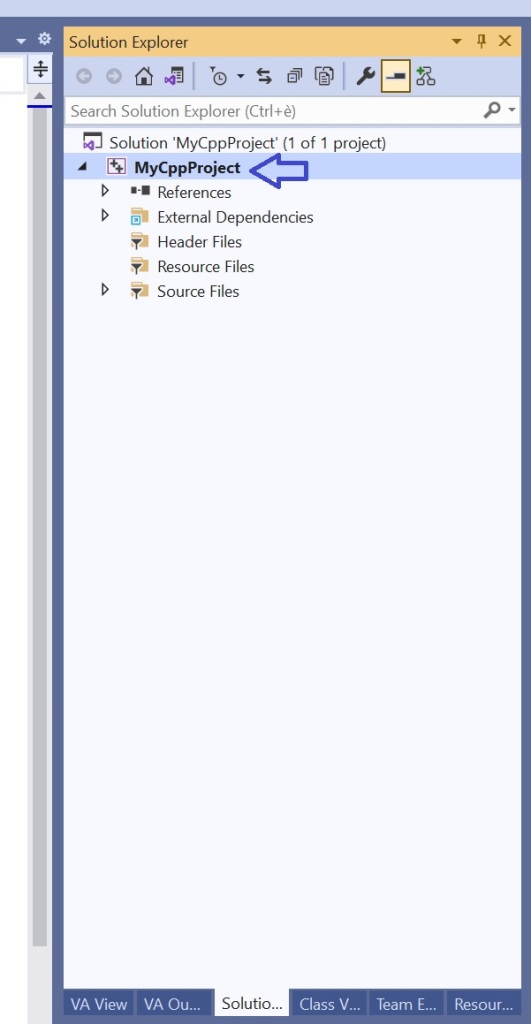

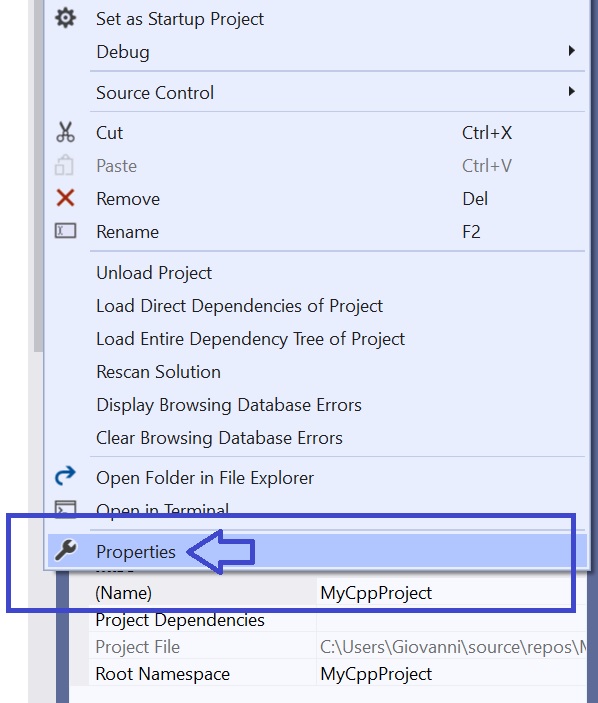

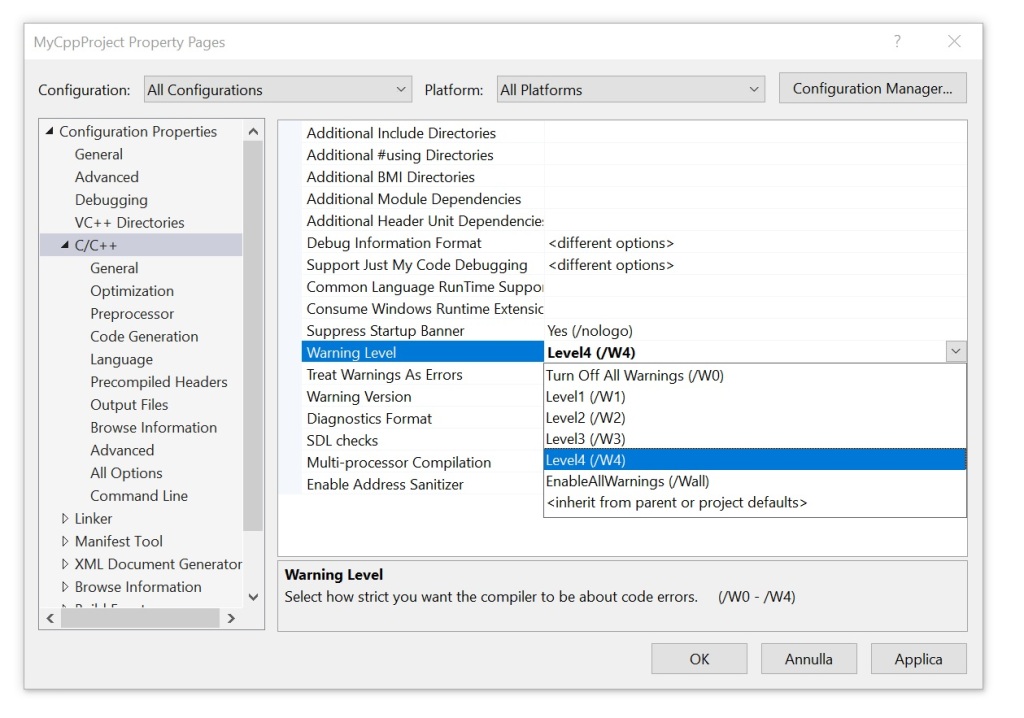

I tried compiling that code with VS 2019 at warning level 4 (which is a good warning level for VC++), and the code compiles successfully, with no warnings emitted by the VC++ compiler.

Of course, I won’t discard VC++, as I consider it the best C++ compiler for Windows (and Visual Studio is my favorite IDE for Windows).

On the other hand, if I add the [[nodiscard]] attribute to the GetSomething function:

[[nodiscard]] int GetSomething()

{

...

then the VC++ compiler does emit a warning message:

warning C4834: discarding return value of function with ‘nodiscard’ attribute

So, should C++ compilers emit warnings on discarded return values by default?

Well, if you think about it, printf returns an int, which I think a lot of programmers discard 🙂

So, if C++ compilers would emit such warnings by default, compiling lots of code that uses printf to print some text to the standard output would result in very noisy compilations.

Well, you may argue that printf comes from C. But I could reply that it’s used a lot in C++ (at least until the recent std::print and related formatting functions added in C++20/23).

Moreover, even focusing on more C++-specific features, even something like operator= overloads return a reference that is many times discarded:

T& operator=(const T& other)

{

...

return *this;

}

Should an innocent assignment like:

trigger a warning??

So, assuming a default [[nodiscard]] policy, that would indeed generate lots of noisy compilation sessions!

On the other hand, adding [[nodiscard]] to many functions and methods can result in very noisy and kind of cluttered code, too.

So, we need to find a balance here.

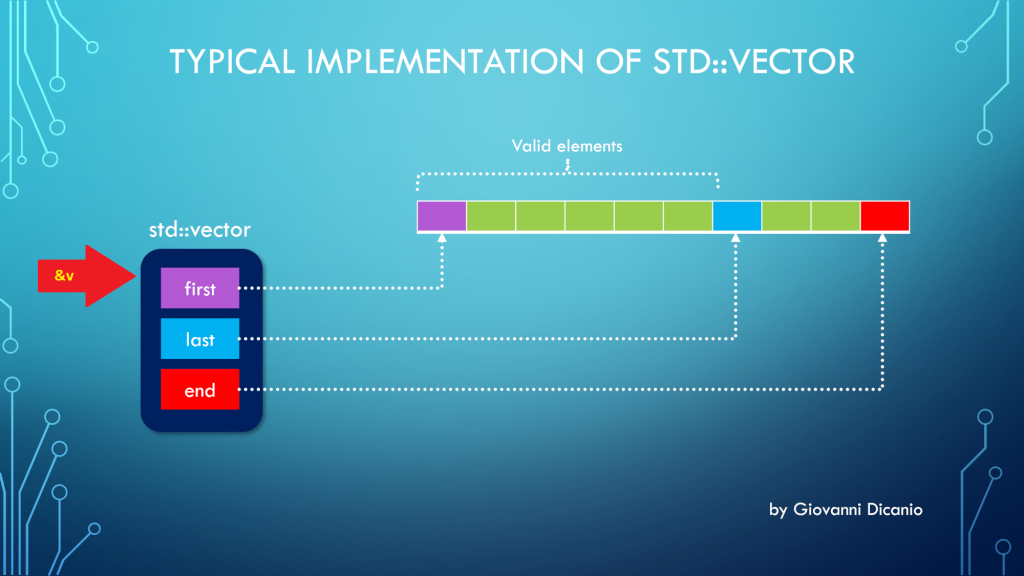

A good alternative could be adding [[nodiscard]] to structs or classes or enumerations that represent an error information or something that shouldn’t be discarded, so the C++ compiler will automatically apply the [[nodiscard]] behavior to functions and methods that return those [[nodiscard]] classes or enumerations. Note that this behavior is already implemented in C++17, and available in C++ compilers like Visual C++ 2019.

Another option I was thinking about is this: Assume [[nodiscard]] behavior as the default, and opt out using another attribute, like [[maybe_discarded]], in cases like the operator= overloads, in which discarding the returned value or reference is perfectly sensible. This would adhere to the philosophy of good defaults. In other words, if you don’t specify anything, you’ll get [[nodiscard]] behavior by default, and warning messages. And in those specific cases when discarding the returned value can make sense, only there you specify an explicit attribute like [[maybe_discarded]].

![C4834 warning message emitted by VC++ 2019 in its default C++14 mode, when the return value of a [[nodiscard]] function is discarded.](https://giodicanio.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/cpp_vs2019_default_cpp14_nodiscard_warning.png?w=974)